I was driving on route 1806, a narrow two-lane highway in North Dakota leading to the town of Canon Ball where members of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe were protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline. The day before, October 28th, I had stopped at a café on my way from Lebanon, North Dakota, and I saw a copy of the “Bismarck Tribune” with the headline “Police oust protesters.” 141 people had been arrested. The Native American tribe was demonstrating against the oil pipeline passing close to their reservation, as there was a risk of their water supply being polluted, in addition to their burial grounds being desecrated. The videos I later saw of the protest were incredibly violent. The way the demonstrators were being beaten and shot at with rubber bullets would not seem out of place close to home. I was only an hour away from the town, so I decided to head there, perhaps out of the selfish feeling that participating in a civil disobedience movement would be a reminder of Beirut; I had already been feeling homesick. But my excitement would prove anticlimactic.

Route 1806

About 40 minutes away from the town, a sign on the road read “Road Closed. Local traffic only.” I drove around the sign and pretended I was local traffic, which meant the many small dead-end alleys leading to farms on each side of the road. Every few minutes the same sign would reappear and I kept ignoring it. Then a line of 6 identical black tinted SUVs with flashing headlights zipped past me in the opposite direction. I tried finding another route to reach the town, but the paper map didn’t show any and there was no phone signal to check online. Then about 10 minutes before reaching the town, huge flashing signs appear in the distance, with countless cars blocking the road. I figured it was the police, and I approached them carefully. As I was halted to a stop, I was surprised to find out it was actually the army, not the police. In full gear too. A soldier stood still in front of my windshield, and another one came to my window, smiling:

– “Hey there, where are you headed?”, she asked.

– “Lebanon”, I lied.

– “This road is blocked. You have to turn around.”

But then what surprised me was that the word Lebanon didn’t seem to raise any questions for her. She just proceeded to give me direction off the top of her head on how to head to Lebanon, South Dakota. I still regret not having taken a picture of the soldiers with their weapons blocking the road. But I was still behaving the way I do in Beirut where one would never point a camera at a policeman or a soldier lest the camera be confiscated and you risk going to jail. Slightly disappointed, I take my mind off the demonstration and head south.

Before reaching Lebanon, I decide to pass by the county library in Gettysburg to do some research, ten minutes away from town. The history book led me to find that the name was not biblical in this case. In 1885, a certain D.M. Boyle came to the land, erected a house, including the first post office, and named it after his hometown of Lebanon, Indiana, which I’ll be visiting in a couple months. While I was busy doing my research, the extremely helpful librarian, Barb, to whom I had explained my trip, was contacting folks whom I should meet, including a local journalist who became interested in interviewing me. Barb also advised that I visit the Dakota Sunset Museum, which shared a door with the library, as there might be further information to get from there.

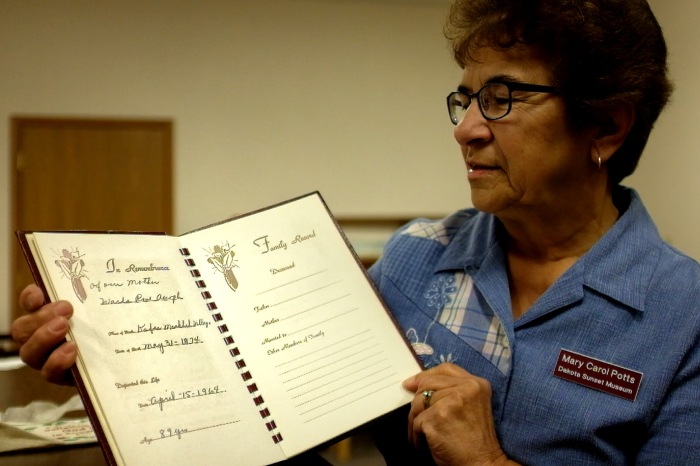

I walked into the museum, and asked the two ladies at the reception, both seeming in their seventies, if they had any historical information about Lebanon. One of these women, her name tag read Mary Carol Potts, approaches me and asks: “Which country are you from?” Now this kind of question might be perfectly fine in our Lebanon, but in the US it is deemed politically incorrect, as one shouldn’t assume that a non-Caucasian is an immigrant. But when I answered the woman, the question made sense. She said: “Yes, I thought you might be from around there. So am I. Both my maternal grandparents came from Lebanon.” To say that this was unexpected coincidence would be an understatement. I never thought I’d run into someone of Lebanese ancestry in that town. I asked to interview her, and she reluctantly agreed.

Mary Carol’s grandfather was born in Beirut in 1857. His name was Georges Assaf. He emigrated to the US in the late 1890s with his father and brother and their name was americanized to ‘Aesoph’. Her grandmother, Warda Elias, came from Kfar Mishki, a small village in Rachaya; everybody called her Rose. Mary Carol’s mother was born in the US and didn’t speak any Arabic; her grandmother always said: “You’re in America now. You have to speak English.” I asked her if she had any stories from the old country, but she mentioned that her grandmother didn’t talk much. She did, however, remember the food. Kibbeh, laban, and yabrak (stuffed vine leaves). With vines not available in South Dakota, she made them with cabbage instead.

Mary Carol Potts showing me the ‘remembrance’ album of her grandmother, Warda Aesoph, née Elias, from Kfar Michki, Rachaya, Lebanon

After visiting with Mary Carol and promising to come back the next day, I headed to the Lebanon Longbranch, the municipality-run saloon that Barb advised me to go to. The streets were dead silent. If it weren’t for the one cow by the town sign, I would have thought everyone had packed and left. I finally found the saloon and walked in. It was empty. An older lady with short curly brown hair greeted me from behind the bar. I was already hungry by then so I asked her if they served any food. She said yes and told me to go to the fridge behind the door to grab a frozen pizza so she could heat it up for me.

We started talking about my trip and her eyes widened. It was her first time meeting someone from another country, and it just happened it was a country she was familiar with. It wasn’t only that this country shared the same name with her town, but rather that just across the street from the bar, there was a cedar of Lebanon planted by the side of the road. It was a gift from your country, she said with a grin.

Hazel McRoberts, manager of the Longbranch saloon.

This caught me by surprise and I headed out to see the tree. When in 1955, the mayors of seven towns called Lebanon went to Beirut for two weeks and came back each with a cedar sapling, the mayor of the South Dakota town was not one of them. The dozens of newspapers I had researched from that year never mentioned him, so there must have been a mistake. But there I was in front of a tree with a massive sign by its side that read: “Cedar of Lebanon. Given to Lebanon, SD by the country of Lebanon. One of two planted, 1955, Mayor WM. Schumacher.”

The problem was, the tree wasn’t a cedar tree at all. I took a few pictures and sent them to Jane Nassar, a landscape designer friend back home, and she said this was a juniper tree. A ‘juniperus virginiana’ to be precise, which is mistakenly called a ‘red cedar’ in some parts of the US. I couldn’t get a clear answer regarding the confusion, but I knew more research would be needed in Lebanon, Ohio when I get there in January. It was that town that received all the trees after they left Beirut. Our country had specified that the saplings had to stay in a nursery for two years to acclimate before being sent back to each town. So maybe there I could figure out why South Dakota was sent a tree, and how come it wasn’t a real cedar.

But Hazel, the barkeeper, was very excited about meeting someone from the country who sent them the tree, and I didn’t have the heart to tell her this was just a plain juniper. So I steered the conversation to a different subject and asked her about the town. She was quick to mention that this was the home to South Dakota’s first outdoor swimming people, in June 1926, a feat they were so proud of that they wrote it on a sign by the highway. But the pool closed down three years ago. It needed a yearly maintenance fee of $10,000 and the town couldn’t afford the money.

I asked why couldn’t the residents contribute a few dollars each towards the budget, which made her laugh: “There are less than 30 people who live in this town. Probably 26. No one could afford it. And there are only 3 kids left who could use the swimming pool in the summer. I came here in 1970 when it was still thriving. We had three banks and several gas stations and grocery stores. When the highway was moved one mile South, all the businesses left. And people started leaving too.”

Later that evening I came back to the bar for dinner. It was also empty. Behind the bar stood a woman with long white hair. Her name was Jan and she said she was expecting me as Hazel told her about my arrival. Our conversation led me to understand what a small town really meant. The bar was managed by three women: Hazel, Jan, and Linda, who were all good friends. Hazel was married to Michael, Jan’s brother, and Linda to Jim, Jan’s other brother. Linda and Jim divorced and Michael passed away. Hazel then married Jim, her former brother-in-law and her friend’s ex-husband; The story felt like a mini soap opera, but they were all friends and, when there aren’t that many people around, one gets drawn to those they see the most.

Aside from tending bar, Jan played the accordion in a country music band along with her brother Jim on the guitar – who also happened to be the head of the town’s municipal board. I asked her if she could play for me and, after hesitating at first, she called Jim who arrived a few minutes later with Hazel. They both played and sang for about half an hour, and the genuineness of their performance was deeply moving; I clapped long and hard after each song.

I came back the next night and the difference was striking. There were about a dozen people drinking at the bar and this was a crowd compared to how it was yesterday. Jan comes in to greet me, turns to the patrons and yells: “Hey everyone, this is Fadi!” A collective “Hey Fadi” greets me back and I was very much in disbelief at how welcoming these strangers were.

Dart night at the Longbranch

I grab a beer – at $1.25 a pint; try finding that price in Beirut – and walk towards the pool table. A man who had apparently heard of my story approaches me and says: “So you’re from Lebanon. Well I grew up in Palestine.” I didn’t give him the chance to continue. I start speaking excitedly to him in Arabic, which I hadn’t done in what seems to be a lifetime. He gave me a puzzled look and then laughed: “Dude… I meant Palestine, Ohio.’

We continued our conversation, in English, and he said he worked at a gas station kitchen, flipping burgers for minimum wage. But his car was of the latest model, and the electronics he had looked expensive. So I asked him how he could afford all of it, and he didn’t hesitate to mention he ‘dealt’ on the side. I thought he meant weed. I was invited to his friends’ place, a husband and wife who recently moved into town, saying it would be different from the Longbranch bar where most people were much older; he was 32. All of them were jittery with dark circles under their eyes. I’m not an expert on drugs, but this couldn’t have been weed. They got agitated when they saw my camera, so I turned it off. Later on, the man from Palestine, Ohio (I’ll call him Matt) and another man whom I recognized from the bar started yelling at each other, and it escalated into a physical fight. The man from the bar, who was heavyset, fell onto my camera bag and I thought my gear was ruined. I quickly excused myself and left.

But before going to the couple’s place, Matt wanted to show me the new land plot he bought. I asked him why he moved to Lebanon, and he mentioned the land prices being low and the town being isolated. The plot was 150 by 50 yards (6270 square meters). “How much do you think I bought this for?”, he asked. “$50,000?”, I guessed. He laughed and said it was only $3,500. Three thousand and five hundred dollars. He refused to have his picture taken, but said that he was trying to get his act together, and he was hoping he could send after his girlfriend and their two kids, aged 13 and 10, from Illinois after he builds a house. He had recently gotten a cross tattoo, in the hopes of motivating himself to become clean.

I learned from that when these small towns get depopulated, the land prices drop. And when there’s no more police force around, it’s a perfect place to live unnoticed. The original town residents were familiar with his side job and they were still welcoming of him as long as he didn’t cause any trouble. I kept wondering if their welcome was genuine or if it was out of helplessness, and whether more clashes were waiting to happen in the future. Hopefully not.

What a wonderful experience! Yes, I have found small towns in USA and other countries too, very friendly.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It sounds like you had an interesting visit to SD to say the least. It will be interesting to find out why the cedar of Lebanon tree is something else. I look forward to meeting you in January here in Lebanon, OH. A local Lebanon, OH expert is John Zimkus. He is a historian in the area and taught middle school here for many years. His number is 513-932-8856 according to white pages.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank, Beccah! Hope he’ll provide some answers, and looking forward to meeting you.

LikeLike

This project is incredible and this story so incredibly interesting not to mention your photographs are beautifully honest. Keep up the fantastic work! I am looking forward to following along your journey.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you, Kaitlyn Jo!

LikeLike

You are very welcome.

LikeLike

Wow, what an extraordinary adventure you’re on! And what a small world. Who would have thought you’d meet someone whose ancestors were born in the same country as yourself!! Amazing. Regarding taking photos of the USA army…I’d say it’s probably a good thing you didn’t. Chances are you would have had the same reaction as at home!!! Loving your road-trip…..besides your objectives, we’re learning a lot more about the USA. Travel safe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Learning a lot myself

LikeLike

Fun stories come from unexpected strangers… The road will give you so many more of those surprises! Enjoy them all!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m still trying to process $1.25 for a pint. You can’t even get a Coke that cheap, much less a beer. I’m in central Texas, and we have juniper trees everywhere, but we call them cedar. It’s been that way my whole life. In fact, the juniper pollen blows around like smoke clouds (it’s so thick) and we all have horrid allergies in Austin, and everybody calls it “cedar fever.” Just a misnomer, I suspect, like Columbus discovering the “West Indies.”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on .

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am completely enamored with your Blog. I enjoy seeing your adventures of these little towns and am truly excited to see what is next. I hope your Homesickness fades soon, I know that is a terrible feeling. Keep your head up and stay safe!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really sorry I missed your comment. Thank you very much for the kind words.

LikeLike

Pingback: Lebanon, Nebraska: A 60-year-old tale of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the CIA, and a death in Jerusalem. | Lebanon, USA

Pingback: Lebanon, Nebraska: A 60-year-old tale of the Arab-Israeli conflict, the CIA, and a death in Jerusalem. | Lebanon, USA

Pingback: Lebanon, Illinois: The day I was given a key the city. | Lebanon, USA

Wow. My wife and I missed you by six months. We were in Lebanon in July of 2016. My great grandfather and his wife and a bunch of my relatives are buried in the local cemetery there. My dad was born in Gettysburg, a few miles away. We visited the museum and the library. I have one second cousin still in the area. By the way, I think my great grandfather and his son, my grandfather poured the concrete for the swimming pool! Tim Geist Sr. owned the first concrete batch plant in Potter County. He died in 1927.

Keep up the good work.

steve

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey there. I am so pleased to read something by a person with ties to Lebanon. My dad was born there i think in 1916 or 17. But I ran across this gentleman’s blog then your remarks completely by accident. I always wanted to go back there as an adult and go find everyone’s burial plots. Wonder if anybody at all is there anymore! My grandad I heard was the town blacksmith plus a drunk that drove his wagon through the town on Friday nights shouting and yelling. When I was a kid and our parents took us there on a road trip I remember just a feeling of sadness. Of course, melancholy seems to run in the family. 😳

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Judy, if you happen to have a chance to revisit, I believe that all melancholy feelings would dissipate once you step into the Longbranch saloon. It’ll feel like home, no where where one is from.

LikeLike

Judy,

I might have posted here before but never got a reply. My name is Dan Vail. We might be related. My father is also named Dan Vail and was born and raised in Lebanon SD. He served in the Navy during WWI and later became a captain on the Los Angels Fire Department. The family business was a livery stable in Lebanon at the turn of the century 19th > 20th of course. My father’s father was also named Dan Vail as is my son and his son. I would like to talk to you or any other Vail from Lebanon or anyone who personally knows any of the Vails from Lebanon as I am running out of time.

LikeLike

Hi Steve, I realize my reply comes about three years too late; apologies for that; I hadn’t been doing my homework checking the blog.

Thank you very much for sharing your story. I loved Gettysburg; the museum was terrific.

It’s unfortunate about the current state of the swimming pool in Lebanon I do hope more decent people will come back to the the town so it would come back to life.

LikeLike

Pingback: Real Lebanons, Fake Cedars. – 1on1

I heard this story on a recent Radiolab Podcast yesterday and found it very interesting. I’ve only read this portion of the blog but will definitely read more. I live in Los Angeles and work in construction. I don’t leave town very often but stories like this take me to those places. Thanks for sharing. Happy trails!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers, Warren. Thank you

LikeLike